You need test results you can trust, and you need them before hardware hits the lab. Hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) and power hardware-in-the-loop (PHIL) compress that learning cycle by closing the loop between your controller and a faithful plant, early and safely. Teams use these methods to catch edge cases, tune protections, and quantify margins without risking converters, machines, or grids.

Results arrive sooner, cost less to obtain, and carry the traceability leaders expect.

Senior simulation engineers, HIL test engineers, power systems engineers, and control systems engineers ask the same question every week about the quickest way to get credible evidence. The answer depends on how much energy must move through the set up, which parts must be exercised, and which risks must be covered. PHIL vs HIL is not a popularity contest, it is a practical choice based on constraints, lab assets, and required fidelity. Clear criteria and practical reasoning help you pick a path that aligns with your schedule, budget, and safety posture.

How HIL testing improves power system validation accuracy

With HIL, your controller hardware couples to a high-fidelity, real-time model of the plant. The simulator integrates differential equations at fixed time steps, exchanges I/O with the device under test each tick, and controls jitter tightly. That determinism reveals closed-loop dynamics that offline simulation hides, especially during trips, saturations, and corner cases. Repeatability improves because test vectors, fault sequences, and sensor imperfections can be reproduced exactly across builds.

Accuracy grows when sensor, actuator, and quantization effects are included, so you evaluate the same limitations you will face in the lab. HIL testing lets you inject stochastic noise, quantize ADC counts, and model PWM deadtime without risking power hardware. Coverage also increases because you can run thousands of runs overnight, then compare outcomes with scripts, dashboards, and reports. Teams often refer to this as hardware in the loop for a reason, since the controller interacts with a plant that behaves like physical equipment while still living inside a deterministic simulator.

Why power hardware in the loop testing matters to engineers

Power hardware-in-the-loop connects a real power device to a simulator through a four-quadrant amplifier so actual volts and amps flow. Engineers validate protection, thermal margins, and interactions with grid or machine models before field energization. Converter prototypes experience realistic source impedance, fault levels, and harmonic content, which exposes issues that small signal tests miss. You see how firmware reacts when a feeder sags, a DC link ripples, or a motor stalls, all without full-scale infrastructure.

Power hardware in the loop matters when you need energy exchange to answer the question at hand, such as current sharing between paralleled modules or ride-through under specified faults. It also matters when standards require physical testing steps you cannot complete with only signal I/O. Lab managers value PHIL because it de-risks commissioning by catching wiring pitfalls, grounding issues, and device interactions with realistic impedances. HIL pulls software bugs forward, and PHIL pulls power issues forward, which saves cost and avoids late surprises.

Core differences between power hardware in the loop and HIL testing

The main difference between power hardware in the loop and HIL testing is that PHIL exchanges power with the device under test through an amplifier, while HIL exchanges signals only through low-level I/O. PHIL validates interactions that depend on energy flow, such as current limiting, short-circuit behaviour, and ride-through, and it exercises protections with realistic fault energy. HIL excels at closing the loop around embedded code, control logic, and estimators without exposing prototypes to electrical stress. Both approaches close the loop in real time, yet the scope, cost, and risk profile are not the same.

PHIL typically needs a regenerative, four-quadrant source, power interface algorithms, and strict safety interlocks. HIL needs deterministic timing, fast I/O, and realistic sensor and actuator models. PHIL test time is often constrained by amplifier ratings, cabling, and power dissipation, while HIL test time is set mainly by simulation speed and model complexity. Many teams pair them: HIL for continuous regression and algorithm tuning, then PHIL for focused campaigns on power behaviour and compliance.

| Aspect | HIL | PHIL |

| Primary objective | Validate control logic, estimators, and embedded software | Validate power-stage behaviour, protections, and energy interactions |

| Physical hardware under test | Controller, I/O, and firmware | Power device, converter, motor, or protection hardware |

| Energy exchange | Signal-level only | Power-level via amplifier or grid emulator |

| Typical risks | Software faults, timing errors | Electrical hazards, component stress |

| Key assets required | Real-time simulator, I/O, timing tools | Real-time simulator, power amplifier, interface algorithms, safety interlocks |

| Best suited for | Regression, coverage, corner cases, early design | Compliance checks, thermal and protection validation, commissioning rehearsal |

| Throughput and coverage | Very high, automation friendly | Moderate, limited by amplifier and safety constraints |

| Cost and schedule pattern | Lower per test, short set up | Higher per test, careful planning and procedures |

How to choose between PHIL and HIL testing setups

Selection gets easier once you align the test with the question, constraints, and acceptable risk. Start from the result you must believe, then work backward to the minimum evidence needed. That evidence might be a time series that proves a controller stays stable, or a thermal profile that shows a module survives faults. A structured look at objectives, safety, fidelity, schedule, and lab readiness keeps the choice grounded.

Clarify the test objective

A crisp objective trims guesswork and points to the correct set up. If the goal is to validate a current regulator, a state observer, or a start-up sequence in firmware, HIL usually fits best. The simulator provides the plant, non-idealities, and event sequences while your controller runs at full speed. You get closed-loop data that proves stability margins, transient response, and robustness.

Questions that hinge on energy flow call for PHIL. Examples include short-circuit ride-through, converter current limiting under hard faults, or valve stress during blocked-rotor conditions. Hardware in the loop without power cannot expose the same thermal, magnetic, or protection dynamics that appear when amps and volts move through copper. Choosing the set up that directly answers the objective keeps time and cost under control.

Assess safety and risk posture

Risk acceptance sets the boundary for PHIL campaigns. High energy levels, rotating machines, and exposed busbars increase hazard severity, which shifts some work to HIL first. A staged plan that proves software safety chains on HIL, then checks power behaviour on PHIL, reduces exposure while preserving learning speed. Clear stop criteria, signage, and rehearsed procedures belong on the checklist.

PHIL should include interlocks, permissives, and verified emergency stops that cut energy quickly. Protective relays, fuses, and fast contactors must be coordinated with simulator limits, amplifier ratings, and device tolerances. Grounding needs attention to avoid nuisance trips, measurement drift, or unexpected current paths. Risk reviews that include the HIL test engineer, the power systems engineer, and the lab manager raise the bar on safety.

Set fidelity and measurement targets

Accuracy requirements drive model order, time step, and instrumentation choices. If you must resolve fast switching harmonics, your simulator and interface must support the required bandwidth. If you only need average-model behaviour, you can choose longer steps, lighter models, and faster runs. Measurement chains should be specified for range, accuracy, and latency so evidence stands up to scrutiny.

Model fidelity benefits from parameter identification, validation against bench data, and controlled injections. Specify how much error is acceptable on key figures such as settling time, overshoot, or current ripple. For PHIL, consider amplifier output impedance and sensor dynamics because they shape what the device under test experiences. For HIL, include ADC quantization, PWM nonlinearity, and timing jitter so the controller sees what it will face later.

Balance cost, schedule, and iteration rate

HIL offers high throughput for iterative tuning, broad coverage, and unattended regression. Model edits compile quickly, test suites run overnight, and results roll up into dashboards for the team. PHIL delivers the confidence that comes from energy exchange, yet each run consumes more set-up time and operator attention. Blending both creates a plan that saves days while still producing high-confidence data.

Use HIL to converge algorithms, verify limits, and prune the test matrix. Move to PHIL for a smaller set of power-focused scenarios that confirm protections, thermal margins, and compliance points. This sequence reduces amplifier hours, shortens wiring cycles, and keeps resource usage sensible. Budget owners gain clear visibility into what is proven, what remains, and what can be deferred.

Confirm lab infrastructure and integration readiness

PHIL requires a four-quadrant amplifier or grid emulator sized for voltage, current, and bandwidth. Cables, connectors, and grounding must be planned to avoid voltage drops, loops, or measurement errors. Cooling, space, and access control matter because they shape how smoothly tests run. Isolation and earthing should be reviewed before any energization.

Interface algorithms link the simulated plant to the amplifier and device under test, so their stability characteristics need review. Coordination with protection devices prevents nuisance trips and protects hardware during faults. HIL infrastructure should also be ready, with deterministic timing, accurate I/O scaling, and logging that captures everything needed for audits. Small investments in fixtures, harnesses, and lab procedures pay back quickly.

A thoughtful selection process avoids rework and makes results easier to trust. HIL builds confidence in control logic and timing, while PHIL confirms behaviour that depends on actual energy flow. Both can live in the same plan, feeding each other with parameters, insights, and scripts. Consistency in objectives, safety, and measurement practice ties the plan together.

When hardware in the loop testing saves development time

Hardware in the loop testing cuts weeks from schedules when control algorithms are not ready for live power.

You can run plant models that mimic converters, machines, and grids, then exercise embedded code at clock speed without risk. Fault injections, sensor failures, and extreme setpoints reveal issues long before you reserve amplifier time. That head start improves software quality, which shortens later campaigns on PHIL.

Teams also gain speed when HIL assets plug into automated regression, version control, and continuous integration. Every code change triggers closed-loop tests, summary plots, and KPIs, which helps leaders authorize releases with confidence. Test engineers maintain curated scenarios that catch known failure modes and verify fixes stay fixed. This discipline frees scarce PHIL resources for the few cases that must involve power.

Common challenges in power hardware in the loop and solutions

PHIL brings real energy to the bench, so it rewards careful engineering. Challenges usually show up at the interface between digital models, amplifiers, and protection systems. Most setbacks trace to stability, scaling, or timing. The good news is that each has a systematic fix that you can plan before the first energization.

- Power interface stability and delay: Loop delay between simulator, amplifier, and sensors can destabilize the interface. Choose an appropriate method such as the ideal transformer method with damping, partial circuit duplication, or hybrid compensation, then tune for phase margin and robustness.

- Amplifier bandwidth and slew rate limits: Limited voltage or current bandwidth can distort fast events, especially during faults. Specify amplifiers with adequate small-signal bandwidth and slew rate, or scale voltage and current through transformers to keep demands within spec.

- Measurement scaling and noise floor: Incorrect scaling, poor shielding, or quantization can corrupt feedback. Calibrate sensors, use differential measurements, add anti-aliasing filters where needed, and verify ADC counts at multiple operating points.

- Protection coordination and safe shutdown: Mismatched thresholds cause nuisance trips or late trips that stress hardware. Define trip levels, dwell times, and reset rules in one matrix, then test them with scripted fault profiles that match expected faults.

- Grounding and common-mode management: Uncontrolled reference paths create circulating currents and measurement drift. Plan earthing points, isolate sensitive circuits, and use proper cable routing to reduce common-mode interference.

- Closed-loop latency and jitter: Variable timing affects duty-cycle updates, estimator performance, and current regulation. Profile end-to-end latency, pin down jitter sources, and set hard limits for simulator step size, I/O update rate, and logging.

Careful preparation keeps PHIL efficient, safe, and informative. A short readiness review before each campaign prevents surprises and protects scarce hardware. Early HIL runs catch software and timing issues so PHIL time focuses on energy behaviour. These habits turn PHIL into a predictable, high-value stage in your validation flow.

How OPAL‑RT supports your PHIL and HIL testing needs

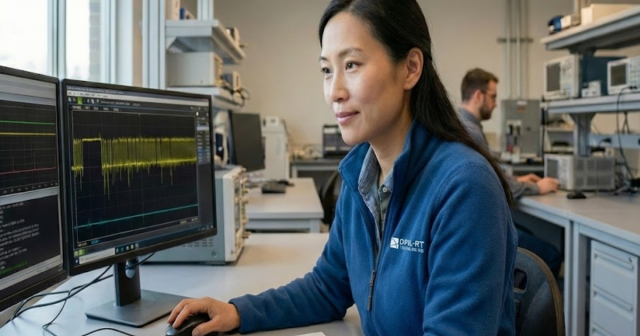

OPAL-RT delivers HIL platforms that combine low-latency execution, precise I/O timing, and scalable compute so your controller runs against a credible plant model. RT-LAB software orchestrates model deployment, test automation, and data capture, giving you traceable evidence for reviews and audits. Toolboxes for power electronics and grids let you model converters, machines, and networks with the fidelity your targets require. Open interfaces support FMI/FMU exchange and Python automation, which helps your team link models, scripts, and lab equipment without brittle workarounds.

For PHIL, OPAL-RT systems integrate cleanly with four-quadrant amplifiers and grid emulators through proven interface algorithms and safe operating procedures. Engineers can start with HIL to tune controls, then switch to PHIL to validate protections, thermal limits, and compliance points using the same scenario files. Modular hardware such as the OP4000 and OP7000 families scales from a single converter to multi-machine microgrids, while FPGA acceleration preserves fast transients and switching effects. Global support teams help you plan tests, review set ups, and troubleshoot issues so your lab time produces reliable evidence. Engineers count on OPAL-RT for repeatable, high-fidelity testing that stands up to scrutiny.

Common Questions

What is the purpose of hardware-in-the-loop testing in control development?

Hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing gives you a safe, repeatable way to validate embedded control systems before physical integration. It closes the loop between your controller hardware and a simulated plant that runs in real time, exposing bugs and timing issues early. You can replicate faults, edge cases, and sensor behaviour that would be risky to test on actual hardware. With OPAL-RT’s simulation platforms, engineers get accurate timing, low-latency I/O, and scalable model integration for dependable results at every development stage.

When should I use power hardware-in-the-loop instead of HIL testing?

Power hardware-in-the-loop (PHIL) is best suited when your validation depends on actual energy exchange, such as testing converter current limits or verifying protection during faults. If you need to see how your system behaves under real voltage, current, or grid conditions, PHIL gives you that level of realism. It’s ideal for validating thermal behaviour, short-circuit response, and compliance scenarios. OPAL-RT provides simulation and interface tools that make PHIL accurate, stable, and safe so you can test with confidence.

Can I use HIL and PHIL together in the same validation workflow?

Yes, many teams use HIL and PHIL in tandem to maximize coverage and efficiency. HIL is used early to validate control algorithms and system logic, while PHIL takes over once it’s time to test energy flow, protection, and thermal response. This sequential approach helps reduce risk, save time, and get the most from lab infrastructure. OPAL-RT’s modular architecture allows seamless transitions between HIL and PHIL, giving your team a consistent, high-performance workflow across both.

How do I know if my lab is ready for PHIL testing?

You’ll need a four-quadrant amplifier or grid emulator, reliable grounding and safety systems, and coordination between simulation tools and power-stage protection. PHIL setups also require careful tuning of interface algorithms and amplifier stability. Before you run live tests, it’s important to verify your system’s timing, latency, and signal fidelity. OPAL-RT supports you with tools, expertise, and integration methods that help you meet lab readiness requirements with accuracy and confidence.

What kind of results can I expect from HIL compared to offline simulation?

HIL gives you real-time, closed-loop responses from your control hardware under simulated plant conditions. Unlike offline simulation, it accounts for actual sensor delays, timing jitter, quantization, and I/O response, which brings your testing closer to how your system will behave in the field. It also supports automation, fault injection, and regression campaigns that aren’t possible offline. OPAL-RT’s HIL platforms give engineers the precision and control to capture meaningful results and accelerate decision-making.

EXata CPS has been specifically designed for real-time performance to allow studies of cyberattacks on power systems through the Communication Network layer of any size and connecting to any number of equipment for HIL and PHIL simulations. This is a discrete event simulation toolkit that considers all the inherent physics-based properties that will affect how the network (either wired or wireless) behaves.