Power electronics modeling and simulation explained for test engineers

Power Electronics

11 / 28 / 2025

Key takeaways

- Power electronics simulation gives test engineers a safe way to stress converters, controllers, and protection logic under conditions that would be costly or risky on hardware.

- The quality of power electronics modeling, including device fidelity, parasitics, and control timing, directly affects the confidence you can place in any simulation or HIL result.

- Structured converter modeling, from clear topology and operating modes to validation against measurements, turns models into reusable test assets instead of one-off design sketches.

- Common challenges such as numerical instability, long runtimes, and misalignment with bench results can be managed through careful solver choices, model simplification, and regular comparison with lab data.

- Real-time platforms and HIL or PHIL setups help extend converter simulation to controller and power hardware testing, enabling teams to build a continuous, traceable validation chain from concept to signoff.

You cannot validate modern power hardware with guesswork anymore. As switching frequencies rise and converter topologies grow more complex, intuition alone becomes an unreliable guide. Test engineers feel that every week, as new devices arrive with tighter margins, stricter safety targets, and aggressive project timelines. Simulation becomes less of a nice-to-have and more of a practical shield that protects projects, teams, and hardware.

What is power electronics simulation and how does it work in practice

Power electronics simulation is the use of numerical models to predict how converters, drives, and related systems behave under electrical and control stimuli. At its core, you replace copper, silicon, and magnetics with equations that represent voltages, currents, and device states over time. The simulator solves these equations at very small time steps to capture switching events, transients, and control actions with useful detail. For a test engineer, this means you can evaluate a scenario in software that would be expensive, slow, or unsafe to repeat on a physical setup.

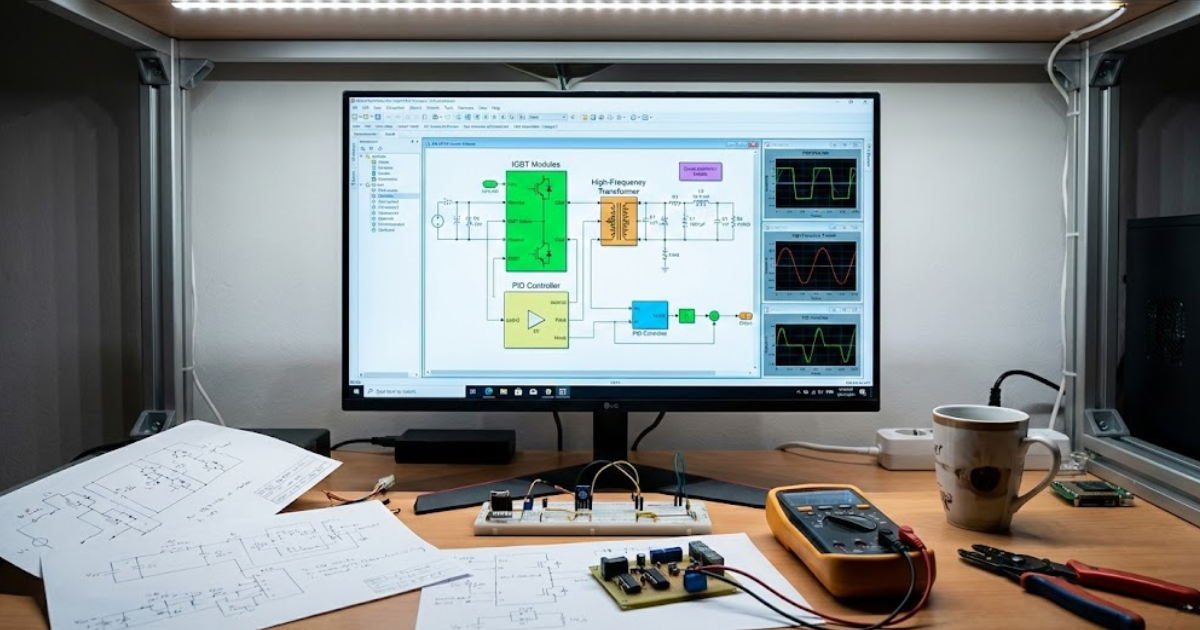

When someone searches “what is power electronics simulation” or “how does power electronics simulation work,” they usually want to understand the practical workflow behind those equations. In most tools, you start by drawing or scripting a circuit that includes converters, filters, machines, and measurement points. You then configure device models, control algorithms, and numerical parameters such as time step, solver type, and stop time. The simulator then marches forward in time, producing waveforms, losses, and state variables that you can inspect in scopes, data logs, or automated reports.

Power electronics simulation supports several levels of fidelity, from simplified average models to detailed switch-level representations. Average models focus on control and system behaviour over longer intervals, which is useful when you care about efficiency trends, control stability, or power quality. Switch-level or electromagnetic transient models focus on individual switching events, dead time, and parasitics such as stray inductance or capacitance. The right choice depends on your validation goal, and many teams maintain both levels so that high-fidelity models are used for critical cases, while lighter models support faster sweeps and automation.

“Simulation becomes less of a nice-to-have and more of a practical shield that keeps projects, teams, and hardware safe.”

Why power electronics simulation matters for your system design

Power electronics simulation matters because decisions you make about topology, control, and protection early in a project can lock in cost and risk later. When you simulate a concept converter under realistic loads and grid or source conditions, you see issues such as saturating magnetics, device overvoltage, or weak stability margins before layout and hardware spend. This early visibility lets you adjust ratings, rework control structures, or refine protection thresholds while change is still relatively easy. You also build a reference behaviour that future hardware tests can be compared against, which helps when debugging later discrepancies.

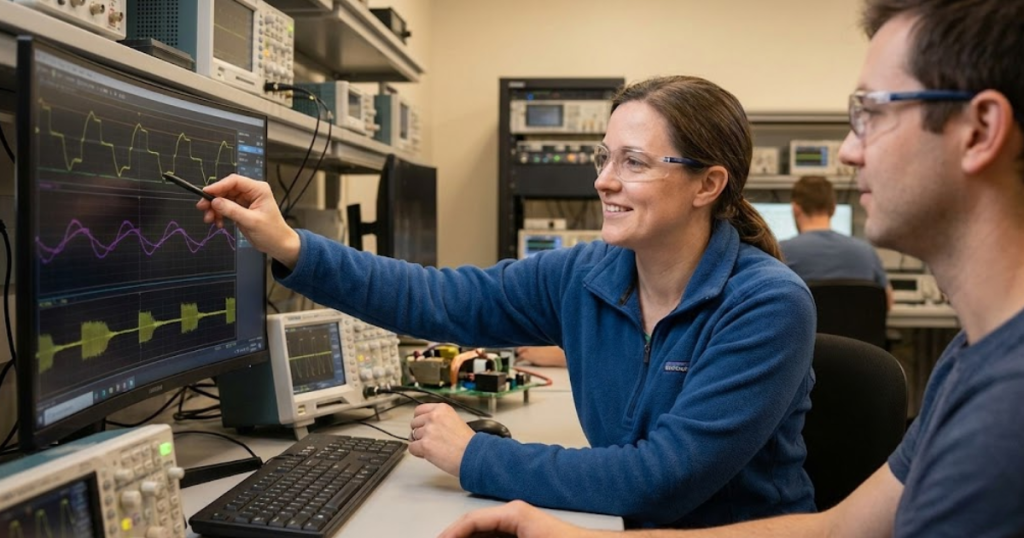

Simulation also alters how you plan and execute validation campaigns. Instead of building a monolithic test matrix directly on hardware, you can split cases into those that must run on physical rigs and those that are better suited for software or hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) benches. HIL connects your real controller to a real-time simulator that runs the plant model with tight timing, so you can exercise the device under test in closed loop without exposing prototypes to extreme events too early.

How power electronics modeling sets your simulation up for success

Good power-electronics modeling determines how trustworthy your simulation results will be long before you press Run. The choices you make about topology detail, device models, parasitics, and operating conditions directly shape waveform accuracy, convergence, and runtime. For a test engineer, this modelling work is often shared with design and control teams, so clarity and traceability matter as much as raw fidelity. Thoughtful model structure gives you confidence that any mismatch between simulation and bench points to assumptions or hardware, not hidden shortcuts in the model.

Poor modeling, on the other hand, can waste weeks by hiding issues or creating non-physical artefacts that send teams in the wrong direction. Missing parasitics, unrealistic control timing, or simplified fault behaviour might all pass an initial review, yet later create confusion when tests fail. A deliberate approach to power electronics modeling helps you turn models into a living reference that evolves with each prototype build and test cycle. That kind of reference supports safer decisions, cleaner collaboration, and more convincing validation reports.

Choose the right modelling approach and level of detail

A first modelling decision is the level of detail that matches your objective. Average models replace high-frequency switching with equivalent sources that preserve voltage, current, and power over a switching period, so they are well suited for control design and efficiency studies. Switch-level models keep track of transistor and diode states, letting you see switching spikes, ringing, and true device stress, at the cost of longer runtimes. If you are planning hardware tests, aligning the model detail with the type of lab experiment you will run later avoids surprises.

Another key choice is the modelling approach itself, such as circuit-level equations, state-space representations, or higher-level component libraries. Circuit-level models feel intuitive for many engineers, since they resemble schematics and support direct reasoning about currents and voltages. State-space or averaged representations can be helpful when you want to carry analytical reasoning into the model and connect it to control design more directly. Whichever approach you pick, documenting assumptions in the model files helps future reviewers understand what each representation can and cannot show.

Represent semiconductor devices with appropriate fidelity

Semiconductor device models have a strong influence on switching-loss estimates, thermal loading, and electromagnetic behaviour. Simple ideal switches help with quick functional checks, yet they hide reverse recovery, output capacitance, and on-state resistance that shape stress on devices and magnetics. More detailed device models include non-linear capacitances, voltage-dependent conduction, and temperature effects that better capture actual behaviour for insulated gate bipolar transistors, silicon carbide devices, or gallium nitride devices. For system design and validation planning, a mix of ideal and detailed models is often the best strategy.

You can also organise device models so that datasheet parameters are explicit inputs. That structure makes it easier to update models when vendors release new information or when you swap device types later in the project. Calibration of model behaviour against either datasheet curves or lab switching waveforms is a practical step that many teams skip, yet it helps you catch inconsistent parameters early. For test engineers, having well-structured device models means you can confidently interpret simulated stress and compare it with thermal or switching measurements collected on benches.

Capture parasitics and layout-sensitive effects

Parasitics such as stray inductance, capacitance, and resistance shape overshoot, ringing, and electromagnetic interference. Even simple additions like small series inductances in commutation loops or parallel capacitances across devices can reveal issues that ideal models never show. These non-ideal elements often reflect layout choices, lead lengths, or busbar design, so close collaboration between modelling and hardware teams pays off. When you include realistic parasitics in the model, your simulated waveforms resemble what an oscilloscope will later show on a prototype.

It is usually not practical to model every physical detail, so you need a structured way to pick which parasitics matter. Focus on loops with high di/dt or dv/dt, such as switching transitions or connection points near magnetics and filters. Short study runs that sweep parasitic values can reveal thresholds where ringing becomes unacceptable or device stress crosses limits. Those results guide layout reviews and test priorities long before high-energy experiments start.

Keep control and plant models consistent

Control and plant models often come from different teams, and mismatches between them are a common source of confusion. Sampling rates, delays, filter settings, and quantisation must line up between controller models and the firmware that will later run on hardware. When simulated control paths use ideal arithmetic or zero delay while the actual controller uses fixed-point arithmetic, finite sampling, and filtering, you risk overestimating stability margins. Aligning digital aspects in models with their future implementation is as vital as matching electrical parameters.

A practical practice is to keep control models close to deployable code, either through code generation or by using shared libraries for filters and logic. That closeness helps you reuse test cases across model-in-the-loop, software-in-the-loop, and HIL stages without rewriting test logic. For plant models, consistency means using the same parameters, initial conditions, and operating modes in both offline simulations and HIL runs. When those alignments are in place, you can trace an issue found in a HIL bench back to either plant or control assumptions instead of wondering which side drifted.

Plan for real-time execution and hardware-in-the-loop

If your team uses hardware-in-the-loop for converter validation, modelling choices must consider real-time constraints from the start. Real-time simulators execute plant models at fixed step sizes that are tied to controller sampling, so computational effort per step must stay within available time. Highly detailed models with many states might run fine offline but miss deadlines on real-time targets, causing overruns that break closed-loop behaviour. Planning a real-time friendly model structure early avoids rushed simplifications later in the project.

You can prepare for real-time execution by limiting stiff dynamics, controlling the number of switching events per time step, and using model reductions in less sensitive parts of the plant. Partitioning the model into subsystems that cleanly map to processing resources or programmable logic can also help. Some teams maintain parallel versions of the plant model, one for detailed offline studies and another trimmed for HIL work, but both share parameters and validation cases. This separation keeps high-fidelity insight available while keeping HIL benches responsive and stable.

Careful power electronics modeling does more than create attractive plots. It builds a shared, auditable basis for decisions about ratings, protection limits, and test coverage. When models capture the physics that matter and expose assumptions clearly, test engineers can plan experiments that genuinely stress the right parts of the system. That structure supports safer, faster, and more persuasive validation, from early prototypes through full qualification.

Key steps and best practices on how to model power converters

Power converter models sit at the centre of most power electronics simulation projects, so they deserve careful structure. A converter model links semiconductor devices, magnetics, filters, and control logic into a unified representation that can be exercised across many operating points. Test engineers rely on these models to simulate faults, transients, and long-duration operating cycles that are challenging to reproduce on hardware alone. Treating converter modelling as a clear, staged process helps you maintain quality as topologies, ratings, and use cases change.

Questions such as “how to model power converters” or “how to structure simulation of converters” rarely have a single perfect answer. Still, most effective workflows share common stages, from defining objectives and operating points to validating models against measurements. Each stage carries its own traps, yet thoughtful choices can keep models stable, credible, and practical for day-to-day use. The goal is not an abstract ideal, but converter models that closely match lab behaviour to guide real decisions.

“Integrating simulation into your R&D and validation cycle means treating models as active test assets, not as one-off design sketches.”

Clarify converter topology and operating modes

A solid converter model starts with a precise definition of topology and operating modes. That seems obvious, yet ambiguous schematics, unlabelled reference directions, or missing operating states often cause problems later. You should define how the converter connects to grids, sources, and loads, including grounding and neutral arrangements, as these affect fault currents and protection behaviour. Identifying which devices can be gated, clamped, or bypassed in different modes sets the stage for realistic sequencing.

Operating modes deserve as much attention as the static schematic. Many converters support multiple modes such as start-up, regular operation, power-limited operation, and shutdown, each with distinct control actions and protection rules. Explicitly modelling these modes and their transitions makes simulations of start-up, ride-through, and fault response much more reliable. From a test perspective, those mode transitions often pose the highest risk, so having them clearly represented in the converter model supports targeted validation.

Define operating points, load cases, and corner conditions

Power converter behaviour can look acceptable at a single nominal operating point yet fail badly at corners. Early in modelling, you should list the range of input voltages, frequencies, load types, and power levels that the converter must handle. This list should include low-voltage ride-through, overload conditions, regenerative operation if relevant, and interactions with connected machines or grids. Each case becomes a scenario that you can script in the simulator and later map to lab tests.

Corner conditions also include thermal and ageing effects that shift device parameters. You might increase junction temperatures in the model to represent sustained high load operation or account for higher resistance from contact wear. These shifts help you see margins erode in ways that a purely nominal model would hide. When you reflect those margins in both simulation and test protocols, your validation plan becomes more realistic and convincing.

Select numerical methods and time steps carefully

The numerical side of converter modelling can be easy to overlook, yet it strongly affects stability and runtime. Solvers must handle stiff switching behaviour, non-linear components, and sometimes multiple time scales between electrical and mechanical parts. Short time steps capture switching events more accurately, but they stretch runtimes and can create an overwhelming volume of data. Longer time steps save computation but risk hiding fast transients or causing numerical oscillations that do not correspond to physical behaviour.

A practical approach is to start with conservative solver settings, then gradually relax them while checking that key waveforms and power balances remain consistent. You can also use different settings for different study types, such as very fine steps for switching transient studies and coarser steps for long-duration efficiency sweeps. Monitoring energy balance, harmonic content, and device stress across solver variations helps you judge which simplifications are acceptable. For HIL targets, these numerical decisions must also respect real-time constraints, as missed deadlines directly impact closed-loop behaviour.

Validate the converter model against measurements.

Even a carefully built converter model remains a hypothesis until it is tested against measurement data. Once early prototypes or previous-generation hardware are available, you can collect key waveforms, losses, and temperature profiles under a selection of test cases. Matching simulated and measured results across multiple metrics is an effective way to uncover missing parasitics, incorrect control timing, or unrealistic thermal assumptions. The objective is not perfect numerical agreement but tight alignment on trends and critical values.

Validation should be treated as an ongoing activity, not a one-time check. As hardware revisions, firmware updates, or new operating modes appear, the converter model should be updated and rechecked. Keeping validation cases scripted and version controlled means you can rerun them whenever a model change occurs, which prevents regressions from slipping through. When stakeholders see a traceable history of model-to-measurement alignment, they treat simulation results with much greater confidence.

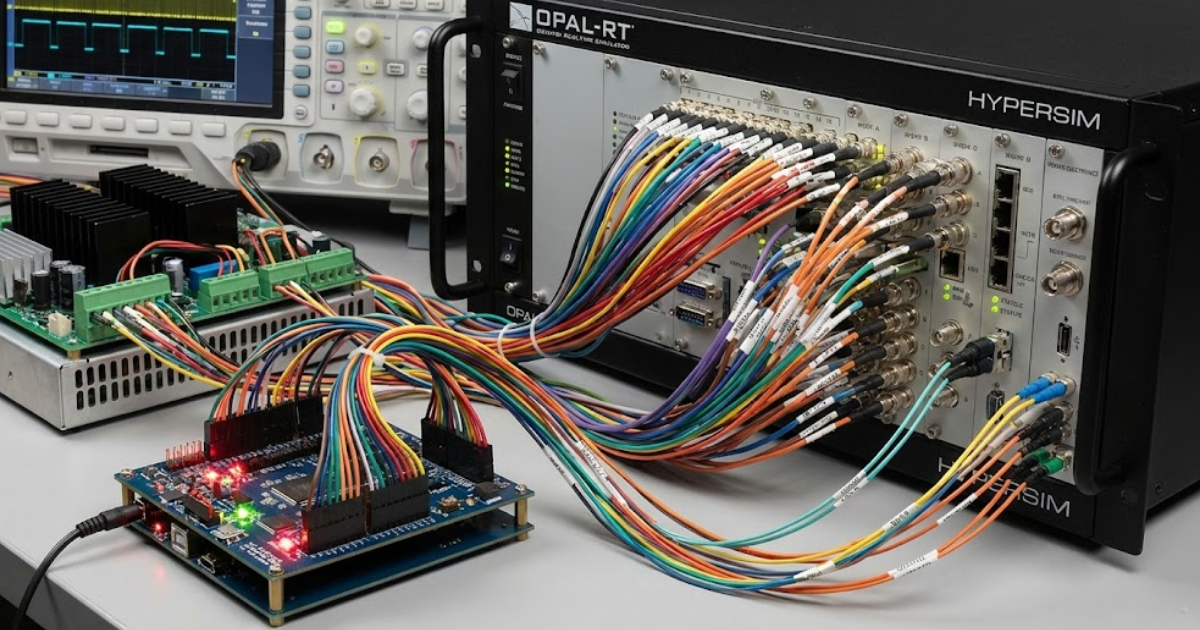

Prepare converter models for hardware-in-the-loop and power hardware-in-the-loop

Converter models used in HIL (hardware-in-the-loop) or power hardware-in-the-loop (PHIL) tests must meet additional constraints. HIL connects a real controller to a real-time simulator, while PHIL adds a power interface that exchanges actual current and voltage with the device under test. These setups require models that are computationally efficient, numerically stable, and structured for clear input-output interfaces. Preparing models with this in mind simplifies the move from offline simulation to controller and power hardware benches.

Interface variables should be well defined: currents, voltages, and status signals that cross between simulator and external hardware need precise scaling, timing, and units. You may also partition converter models so that fast-switching parts run on dedicated processing resources, while slower dynamics sit on general-purpose processors. Anti-alias filters, quantisation, and measurement noise can be added to close the gap between simulation signals and what sensors actually provide. These additions make HIL and PHIL tests more representative of future lab setups, which supports smoother validation.

| Step | Primary goal | Typical inputs | Key checks for test engineers |

| Define topology and modes | Capture structure and state transitions | Schematics, wiring diagrams, operating states | Mode logic clear, no ambiguous conduction paths |

| Specify operating points and cases | Cover nominal and corner conditions | Ratings, grid data, load profiles | Cases mapped to planned lab tests and safety reviews |

| Choose numerical methods and time steps | Balance accuracy and runtime | Device speeds, switching frequencies | Stable waveforms, acceptable run times, energy balance |

| Validate against measurements | Align model with physical behaviour | Oscilloscope traces, loss data, temperatures | Trends match, key limits consistent with hardware |

| Prepare for HIL and PHIL use | Support real-time and power testing | Controller specs, HIL/PHIL interface details | Meets step deadlines, clear I/O definitions |

Thoughtful converter modelling gives you a structured way to link equations, code, and hardware in a coherent flow. When steps from topology definition to HIL preparation are explicit, teams can share ownership of models without losing clarity. The result is a converter representation that supports design, control, and test activities with the same underlying assumptions. That consistency shortens investigations, protects hardware, and raises confidence in every simulation run you launch.

Common simulation of converter challenges and how to address them

Simulation of converters offers powerful insight, yet specific recurring issues can slow projects or distort results. Many of these challenges only appear after models grow complex, test cases multiply, or HIL setups are introduced. Test engineers are often the first to spot these problems, since they sit at the intersection of models, controllers, and lab expectations. Recognising common pitfalls in advance helps you plan mitigations so that simulations remain a help rather than a source of confusion.

Some challenges stem from numerical issues, such as stiffness or event handling near switching edges. Others come from mismatched assumptions between teams, for example when control code evolves faster than plant models. There are also issues of scale: models that behave nicely in a single case can start misbehaving across large automated test suites. A clear view of typical problems makes it easier to keep converter simulation aligned with practical validation goals.

- Numerical instability near switching events: Converters often show oscillations or divergent waveforms when time steps are too large or solver settings do not match switching dynamics. You can usually calm these issues by refining time steps around events, adjusting device models, or adding small damping elements that reflect physical resistances.

- Excessive simulation time for long-duration tests: Long runs such as thermal cycles, grid profiles, or drive cycles can take many hours with detailed switch-level models. A typical approach is to switch to averaged or simplified converter models for these sweeps while reserving detailed models for shorter, high-stress cases.

- Convergence problems during start-up or fault cases: Non-linearities and rapid topology changes during start-up, shutdown, or faults can cause solvers to stall. Splitting sequences into staged events, smoothing specific parameter changes, or improving initial conditions often helps solvers find a stable path.

- Misalignment between simulated and measured waveforms: Differences between offline plots and oscilloscope captures may come from missing parasitics, inaccurate control timing, or unmodelled measurement paths. Reviewing assumptions about sensors, filters, wiring, and delays usually narrows the gap and restores trust in the model.

- Difficulties modelling protection and fault logic: Protection functions interact with both fast electrical transients and slower decision logic, which can be hard to represent in a single model. Using clear state machines, explicit timers, and realistic sensor behaviour makes protection studies more reliable and easier to compare with bench testing.

- Scaling issues when moving to hardware-in-the-loop: Models that run comfortably offline may be too heavy for real-time platforms, causing overruns or lost fidelity. Early performance profiling and selective model reduction keep HIL benches responsive without discarding essential dynamics.

These challenges are not signs that simulation is failing you, but signals that certain assumptions or numerical settings need adjustment. Treating problems as prompts to refine models, rather than as reasons to doubt the overall approach, helps teams stay constructive. As you collect experience resolving issues, you can turn them into guidelines for future projects and new colleagues. Over time, converter simulation becomes a stable component of your validation practice rather than an unpredictable source of friction.

Selecting tools and platforms for power electronics simulation and converter modeling

Choosing tools and platforms for power electronics simulation and converter modeling shapes who can participate in model development, how easily you can reuse assets, and how soon you can reach real-time testing. Test engineers benefit from platforms that link offline studies, HIL benches, and power hardware setups with minimal manual rework. A good starting point is to list your required interfaces, such as analogue, digital, and communication links, along with timing constraints from controllers and protection devices. You can then evaluate which simulation platforms align with those needs without forcing awkward workarounds.

Beyond raw performance, model exchange and interoperability matter greatly. Teams often use several modelling environments over a project life cycle, so standards-based interfaces, import options, and co-simulation links reduce duplication of effort. Licensing models and hardware footprints also need attention, especially when you plan to run multiple benches or share setups across labs or partners. Finally, consider how each platform supports automation, scripting, and regression testing, because simulation that cannot be automated tends to be underused in busy validation cycles.

Integrating simulation into your R&D & validation cycle

Integrating simulation into your R&D and validation cycle means treating models as active test assets rather than one-off design sketches. Early concept studies can feed directly into requirements and safety reviews when simulation results are captured in structured reports. As designs mature, those same models can be extended to include detailed switching behaviour, protection logic, and communication paths. Test engineers then reuse them to pre-qualify test plans, tune HIL benches, and analyse unexpected hardware results.

A practical integration pattern starts with offline models for concept and control design, then moves through software-in-the-loop, controller HIL, and, when needed, PHIL or other power benches. At each stage, the goal is to reuse models, parameter sets, and test scenarios rather than rebuild them from scratch. Version control and traceable configuration management help teams determine which model revision corresponds to which set of lab results. When this chain is in place, your validation cycle gains a consistent technical narrative from first simulations to final qualification.

How OPAL-RT can help you accelerate power electronics simulation and modeling

OPAL-RT focuses on helping engineers bring power electronics ideas into hardware with fewer surprises and less wasted time. For test engineers, this starts with high-fidelity real-time simulators that can execute detailed converter and grid models within microsecond time steps, while still leaving enough headroom for automation and data logging. Those systems connect cleanly to controllers under test through analogue, digital, and communication interfaces, so you can apply the same converter models across offline studies, HIL benches, and power stages. That continuity makes it easier to correlate simulated and measured behaviour without having to rewrite models for each bench.

OPAL-RT also supports power hardware testing approaches that mix real-time simulation with controlled power stages. This lets you send actual current and voltage to devices under test while simulating the rest of the plant digitally, which improves safety and repeatability for fault and corner-case studies. For teams juggling multiple projects, OPAL-RT platforms are designed to scale across benches and to integrate with standard automation scripts so that test sequences can be reused and shared. That combination of real-time performance, openness, and practical lab focus is what earns OPAL-RT trust as a long-term simulation partner for power electronics teams.

Common questions

What is power electronics simulation in simple terms?

Power electronics simulation is the process of representing converters, drives, and related circuits with mathematical models so you can study their behaviour without energising hardware. Instead of measuring currents and voltages with probes, you calculate them numerically while controlling time steps, device parameters, and operating conditions. This gives you access to internal states that are hard or impossible to measure on benches, such as detailed switching losses or internal node voltages. For a test engineer, the main benefit is the ability to explore risky or extreme scenarios safely, then carry those insights into lab test plans.

How does power electronics simulation work step by step?

Power electronics simulation usually begins with building a circuit or system diagram that includes converters, sources, loads, sensors, and controllers. Each component is assigned a model, which may be ideal or detailed, and configured with parameters such as inductance, capacitance, device ratings, and control gains. You then choose a numerical solver, define a time step, set initial conditions, and specify how inputs like grid voltage or load torque will change over time. Once the run starts, the simulator repeatedly solves the model equations, updating currents, voltages, and control states at each time step, and records the results for inspection or automated evaluation.

How to model power converters for reliable validation?

Power converter models for validation should start from a clear topology and target operating cases, then add enough detail to capture switching stress, control dynamics, and protection events. Device models need to reflect real ratings and behaviour, while parasitics and layout-sensitive elements should be included in parts of the circuit that experience high di/dt or dv/dt. Control logic must match sampling, filtering, and timing used in firmware so that stability and transient responses behave realistically. Finally, you validate the model against measurements from prototypes or earlier hardware, adjust parameters until trends align, and keep those validation cases under version control so they can be rerun after any change.

What is hardware-in-the-loop testing in power electronics?

Hardware-in-the-loop testing in power electronics connects a real controller or device under test to a real-time simulator that executes a plant model of the converter, grid, or drive. The controller sees voltages, currents, and status signals that resemble those in a physical setup, while its outputs drive the simulated plant through analogue, digital, or communication interfaces. This setup lets you test firmware, protection logic, and state machines under many conditions without assembling full hardware rigs for each case. For test engineers, HIL offers a path to higher test coverage, safer fault testing, and earlier detection of timing or integration issues.

When should you consider power hardware-in-the-loop for converter testing?

Power hardware-in-the-loop becomes attractive when you need to see how actual power devices behave under complex electrical conditions without exposing them to uncontrolled full-scale events. In this approach, a power interface sits between a real-time simulator and the device under test, exchanging controlled voltage and current while the rest of the system remains modelled digitally. The method is particularly useful for fault studies, grid-event replay, and verification of protection thresholds where both electrical and thermal stress matter. Test engineers gain the ability to study severe events repeatedly while keeping equipment within safe limits, which strengthens evidence for design signoff.

EXata CPS has been specifically designed for real-time performance to allow studies of cyberattacks on power systems through the Communication Network layer of any size and connecting to any number of equipment for HIL and PHIL simulations. This is a discrete event simulation toolkit that considers all the inherent physics-based properties that will affect how the network (either wired or wireless) behaves.