9 Motor drive fault injection scenarios for controller validation

Automotive

01 / 29 / 2026

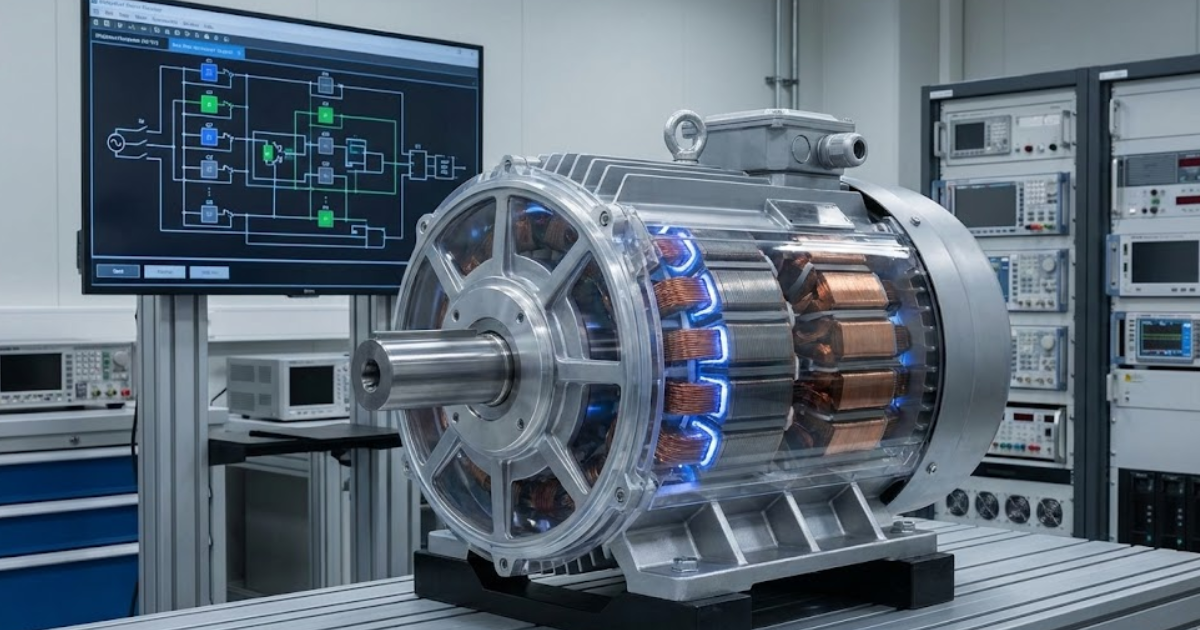

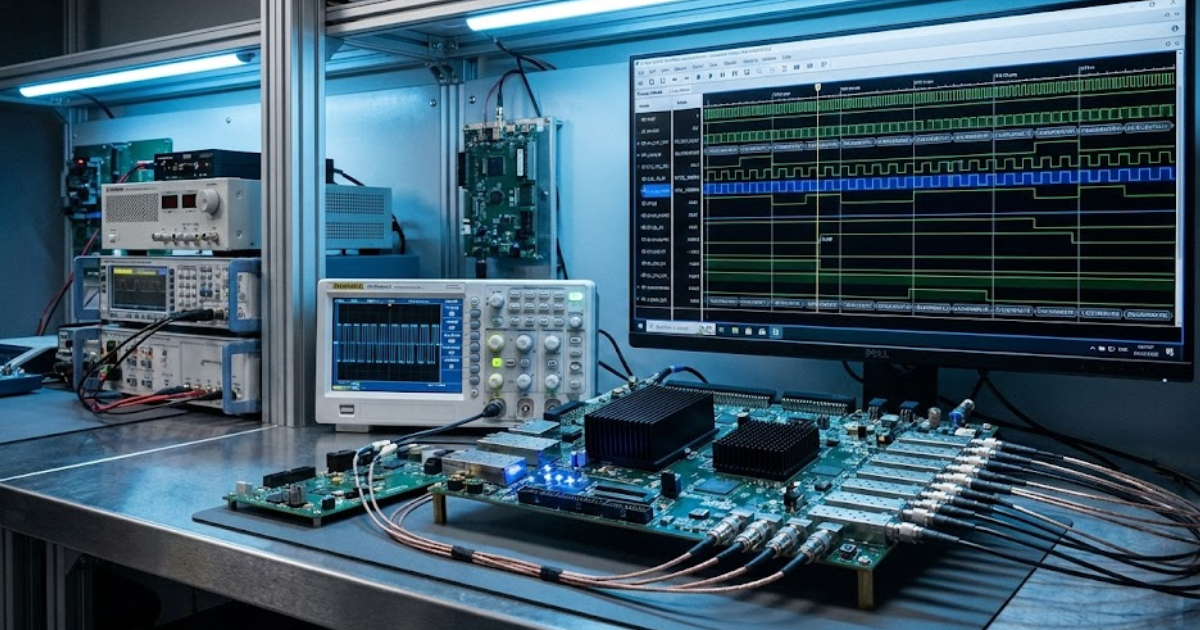

Fault injection shows how a controller reacts when the inverter stops following commands. You measure detection time, control stability, and the path to a safe state. A tight test suite catches faults that commissioning never triggers. Hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) lets you run those tests without sacrificing power hardware.

Complex drives fail in more ways than a single overcurrent trip. Multiphase machines and high bandwidth control leave less margin for messy protection logic. Repeatability matters because firmware changes are subtle. Fault injection gives you the same disturbance, at the same millisecond, on every run.

“Replayability matters as much as severity.”

What controller validation requires from motor drive fault injection

Controller validation needs faults that are repeatable, time-stamped, and tied to explicit pass or fail limits. Each injected event should prove detection, stable control action, and a safe end state. Logs should capture trigger time, key signals, and state transitions.

Hold a fixed operating point and vary one fault parameter at a time. A simple check is constant torque at mid-speed while you add a 5% current sensor offset and watch regulation and torque estimate. Repeat at low speed where the observer carries more weight. The contrast exposes protection logic that depends on one operating corner.

9 motor drive fault injection scenarios to test

These nine scenarios cover energy, switching, sensing, and timing faults seen in drive programs. Each one supports pass criteria stronger than a simple trip. Run every fault at two operating points, such as low speed high torque and high speed light load. Keep the injected waveform identical across revisions.

1. Single-phase open circuit during steady torque operation

A phase open forces current to reroute and can push phases to their limits. Trigger the open at 30% rated torque and steady speed, then log detection time and current limiting. Pass criteria include bounded torque error and a clean transition to your fault state. Repeat near base speed to check stability with less voltage margin.

2. Single-phase short circuit at inverter output

A phase short is high energy and tests protection timing. Inject a short at the inverter output model and confirm the controller blocks gates before the current exceeds your threshold. Verify the order of PWM shutdown, contactor commands, and fault latching. Repeat at two DC link voltages so detection is not tuned to one bus level.

3. Multiple-phase loss in multiphase motor architectures

Drop two phases at once on a 12-phase machine and verify current references shift to healthy phases. Set a de-rated torque target and confirm thermal estimates match the new loading. A solid implementation keeps torque smooth while respecting per-phase current limits. OPAL-RT HIL with FPGA timing lets you replay coupled machine behaviour and tune reconfiguration logic safely.

4. DC link voltage sag and complete DC bus dropout

Apply a DC link sag step, such as 20% drop in 5 ms, and watch the voltage limiter and current control interact. A pass case degrades torque smoothly and stays stable. A full dropout should move to coast or controlled stop, based on your system rules. Repeat under regeneration to confirm the controller avoids commanding a negative voltage it cannot produce.

5. Gate driver misfire, causing uncontrolled switching states

Misfire occurs when the commanded switching and the actual switching disagree, which can cause rapid overcurrent. Model a stuck-high or stuck-low gate on one device and confirm that detection does not depend on one symptom. Verify the controller avoids repeated restart attempts that add thermal stress. Shift the misfire timing within the PWM period to check blind spots.

6. Current sensor offset, noise, or signal loss

Current sensing faults look small until they bias the torque and protection thresholds. Inject a slow offset ramp, then a sudden step, and confirm plausibility checks trip before error integrates. A brief signal loss should not crash loops when samples freeze, drop to zero, or go invalid. Noise injection should prove that filtering does not add lag that destabilizes regulation.

7. Resolver or encoder failure affecting position feedback

Position feedback faults can destabilize field-oriented control fast, especially near zero speed. Freeze the angle signal for 20 ms and verify a controlled stop or fallback estimator starts without current spikes. A swapped sin and cos channel fault tests plausibility checks and sign conventions. Repeat at high speed to confirm that overspeed protection works when angle tracking collapses.

8. Thermal protection faults from inverter or motor overheating

Thermal faults test how you apply limits, not just the trip point. Force a temperature estimate jump across a derate threshold and confirm torque limits apply smoothly with no oscillation. A second test forces critical overtemperature to check shutdown behaviour and restart lockout rules. Pair the fault with high torque so protection runs under stress.

9. Control task overrun or missed real-time execution cycle

Timing faults stay quiet until they ruin stability, especially with tight current loop deadlines. Inject a missed control cycle and verify watchdog, state machine, and PWM update rules give a predictable outcome. Add jitter, such as a 200-microsecond delay every 10 ms, to expose integrator windup and observer drift. This test proves the controller failsafe when CPU load spikes.

“Shift the misfire timing within the PWM period to check blind spots.”

| Fault scenario | What the test should prove |

| 1. Single-phase open circuit during steady torque operation | Imbalance is detected fast and current limits prevent torque runaway. |

| 2. Single-phase short circuit at inverter output | Protection acts before limits are crossed and shutdown order is consistent. |

| 3. Multiple-phase loss in multiphase motor architectures | Healthy phases share current safely and derating matches thermal limits. |

| 4. DC link voltage sag and complete DC bus dropout | Voltage saturation is handled cleanly and the drive reaches a safe state. |

| 5. Gate driver misfire causing uncontrolled switching states | Misfire is identified reliably and restart loops are blocked. |

| 6. Current sensor offset, noise, or signal loss | Bad signals are flagged and current control stays stable. |

| 7. Resolver or encoder failure affecting position feedback | The drive exits position control safely and avoids overspeed and spikes. |

| 8. Thermal protection faults from inverter or motor overheating | Derating is smooth and critical trips block unsafe restart. |

| 9. Control task overrun or missed real-time execution cycle | Watchdogs force a known state when timing slips or jitter appears. |

How to prioritize fault scenarios for HIL-based controller testing

Start with faults that can damage hardware in one event, then move to faults that erode performance over time. Short circuits, gate misfires, and DC bus dropouts come first because timing is everything. Sensor and feedback faults come next because they can mask heating and torque error. Timing faults finish the set by proving the software failsafe under load.

A simple scoring method uses stored energy, observability, and required recovery action to rank tests. That approach keeps the plan honest when lab time is tight. OPAL-RT is most useful once you need deterministic timing and exact replay across many controller builds. Disciplined fault injection builds confidence because it replaces surprises with measurements.

EXata CPS has been specifically designed for real-time performance to allow studies of cyberattacks on power systems through the Communication Network layer of any size and connecting to any number of equipment for HIL and PHIL simulations. This is a discrete event simulation toolkit that considers all the inherent physics-based properties that will affect how the network (either wired or wireless) behaves.