10 Common electrification validation mistakes and how to avoid them

Power Electronics

01 / 15 / 2026

Key Takeaways

- Timing margin and I/O latency should be treated as pass fail requirements.

- Plant fidelity should match the loops, limits, and faults you will validate.

- Interface checks and fault triggers should be verified before adding complexity.

Electrification validation will only hold up when hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) results match hardware behaviour. Many electrification validation mistakes stay hidden until timing and I/O hit real constraints. A controller that looks stable on a desktop plot will ring once ADC delay matters. Catching HIL pitfalls early saves weeks and prevents false pass results.

Real-time simulation errors usually come from time steps, interfaces, or missing limits. A mathematically correct model will still fail a fixed step deadline. Neat wiring still injects unit or sign faults through one channel. Treat the HIL bench like a measurement instrument, then every mismatch becomes actionable.

“Real time simulation is a timed system, not a replay.”

Why electrification validation fails even with advanced HIL setups

Validation fails when results do not repeat with the same code and wiring. Timing slips and hidden delays will create false stability or false faults. A pass then proves only your bench setup, not your control logic. Test confidence falls fast once that gap shows up.

A speed loop passes offline, then trips because the ADC (analogue to digital converter) sample arrives one PWM (pulse width modulation) period later than assumed. That delay shift cuts phase margin and turns a stable loop into a limit cycle. Treat mismatch as measurement and verify task time, I/O latency, and solver stability before tuning gains. Tight basics make fault tests and thermal limits meaningful.

10 Electrification validation mistakes that undermine test confidence

Most HIL pitfalls trace back to mismatched timing, missing physics, or unverified interfaces. Each mistake has a quick check you can run on the bench within a day. A 20 kHz current loop that looks calm offline will oscillate when deadlines slip. Start with the first failure you can measure.

1. Treating real-time simulation as offline model replay

Real-time simulation is a timed system, not a replay. A plant that looks fine at 1 ms offline will fail at 50 µs. Fixed step execution and I/O delay will shift loop phase and noise floors. Freeze step size early, model delays, and profile execution margin.

2. Accepting unstable solver behaviour as a modelling limitation

Solver instability is a validation defect, not a modelling quirk. A diode commutation spike will blow up a naive state update and fake a control fault. Tuning around numerical ringing hides the real loop issue you must fix. Choose a stable discrete solver, break algebraic loops, and verify stability margins.

3. Simplifying power electronics beyond control loop relevance

Simplifications fail when they remove dynamics your loops must handle. An ideal inverter hides deadtime, ripple, and current sensor quantization. Your current regulator will pass offline, then spike on hardware. Keep inverter delays and limits that match your sensing chain.

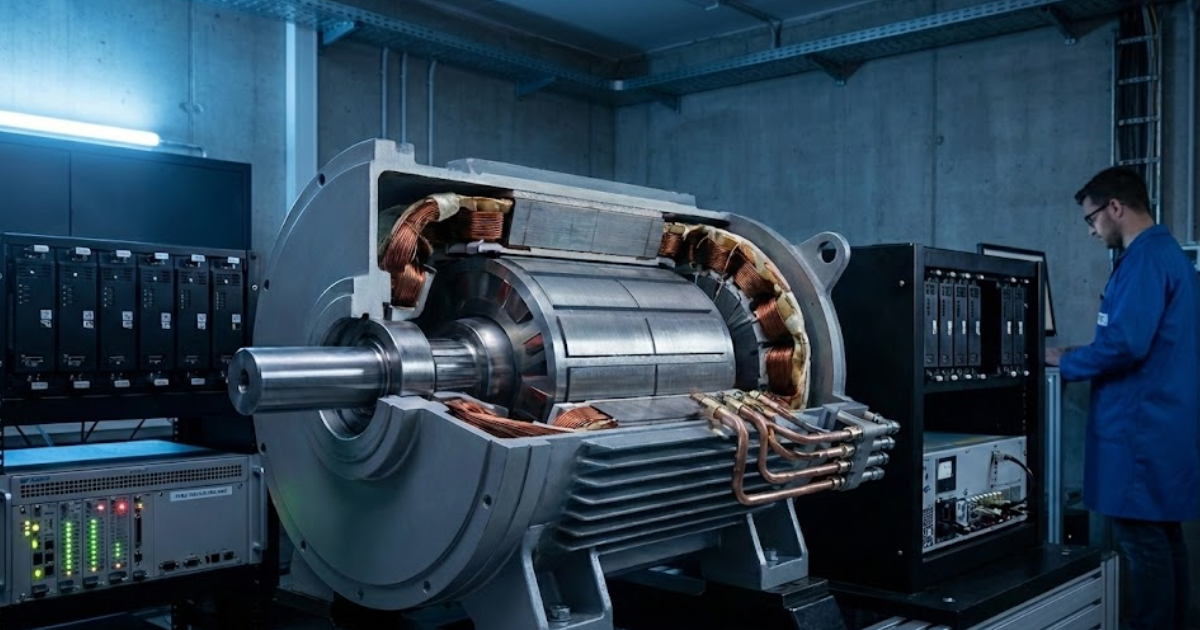

4. Ignoring electromagnetic coupling effects in multiphase machines

Multiphase machines include coupling that shapes faults and observers. A coupled 12-phase permanent magnet synchronous machine (PMSM) will pull current into healthy phases during a phase open. A decoupled model will miss torque ripple and cross currents. Validate coupling terms even when the plant runs on a field programmable gate array (FPGA) with OPAL-RT.

5. Testing nominal operating points instead of fault conditions

Nominal points hide cases that trip protection and saturate loops. A 15% DC bus sag will trigger windup and current spike. Fault paths expose limiters, observers, and thermal derates. Run fault injections early and verify anti-windup and trips.

6. Misaligning control sampling rates with hardware execution

Sampling timing sets delay, and delay sets stability margin. An ADC sample landing mid PWM period shifts the effective phase. Rate mismatches will alias ripple into the control band and create false oscillation. Document the timing chain, align clocks, and measure jitter at pins.

7. Trusting plant models without hardware interface verification

Interfaces break tests faster than plant physics. A sign flip on a current channel makes feedback positive. Plots still look plausible while protection trips and limits clamp. Prove units, scaling, and offset with known stimuli before closing the loop.

8. Scaling test complexity without validating determinism margins

Complexity steals time from your fixed step budget. High-rate logging will push a stable case into overruns and jitter. Jitter then shows up as noise, ripple, or false faults. Keep margin, throttle logs, and move non-critical tasks off the real-time core.

9. Separating control validation from power hardware constraints

Control code lives inside hardware limits, not ideal maths. One timer count of PWM resolution will cause duty chatter. Deadtime, quantization, and saturation will reshape loop behaviour. Model those limits and test with the numeric format you ship.

10. Assuming FPGA use automatically guarantees model fidelity

FPGA timing will hide problems if the plant is wrong. A back EMF constant off by 20% will skew torque estimates. Determinism will make bad parameters look stable and repeatable. Sweep operating points and trace every parameter back to a source.

| What goes wrong | What will tighten your tests |

| 1. Treating real-time simulation as offline model replay | Design for fixed step timing and measured I/O delays. |

| 2. Accepting unstable solver behaviour as a modelling limitation | Start control tuning only after solver stability checks pass. |

| 3. Simplifying power electronics beyond control loop relevance | Keep inverter limits and delays your loops will see. |

| 4. Ignoring electromagnetic coupling effects in multiphase machines | Model coupling so faults match measured phase interactions. |

| 5. Testing nominal operating points instead of fault conditions | Validate limiters and protection under fault stress. |

| 6. Misaligning control sampling rates with hardware execution | Align sampling and task timing so delay stays predictable. |

| 7. Trusting plant models without hardware interface verification | Confirm sign, scaling, and units on every channel. |

| 8. Scaling test complexity without validating determinism margins | Keep timing headroom so logging does not create jitter. |

| 9. Separating control validation from power hardware constraints | Add PWM and numeric limits so code matches target. |

| 10. Assuming FPGA use automatically guarantees model fidelity | Validate parameters so determinism does not hide bad physics. |

How to prioritize fixes across modelling, hardware, and test workflows

Start with repeatability, then add fidelity. Prove the step budget and I/O timing, then lock scaling and sign, then tune control, then run faults. The order stays stable across motor drives, converters, and battery systems.

“Fixing physics on top of a timing problem wastes effort.”

A practical sequence starts with a minimal plant that still exercises the full control path, including ADC timing and PWM update points. Add complexity only after the same case reruns with matching waveforms inside a tight tolerance. Keep a short checklist for every new model or test case: timing margin, interface checks, solver stability, and fault triggers. OPAL-RT helps you run that workflow in real time, but discipline in timing, interfaces, and physics earns trust.

EXata CPS has been specifically designed for real-time performance to allow studies of cyberattacks on power systems through the Communication Network layer of any size and connecting to any number of equipment for HIL and PHIL simulations. This is a discrete event simulation toolkit that considers all the inherent physics-based properties that will affect how the network (either wired or wireless) behaves.